Live Wires

There have been many upheavals in the art world in the last decade or so; one development that has not received the attention it deserves has been the quiet, but no less significant assertion of what one could call a vernacular sensibility. This is the long view from the hinterlands of the subcontinent, looking in and existing tangentially to the ‘mainstream’. The difference here is not an absolute one, but one of degree; – sharing many of the preoccupations that mark the mainstream and its metropolitan centers, yet existing at a slight remove from it, this unique subjectivity is grounded in unorthodox appropriations and parodic transformations of the languages and techniques that comprise the dominant aesthetic paradigms of the last century, often finding their equivalents within the mythopoetic spaces of local cultures.

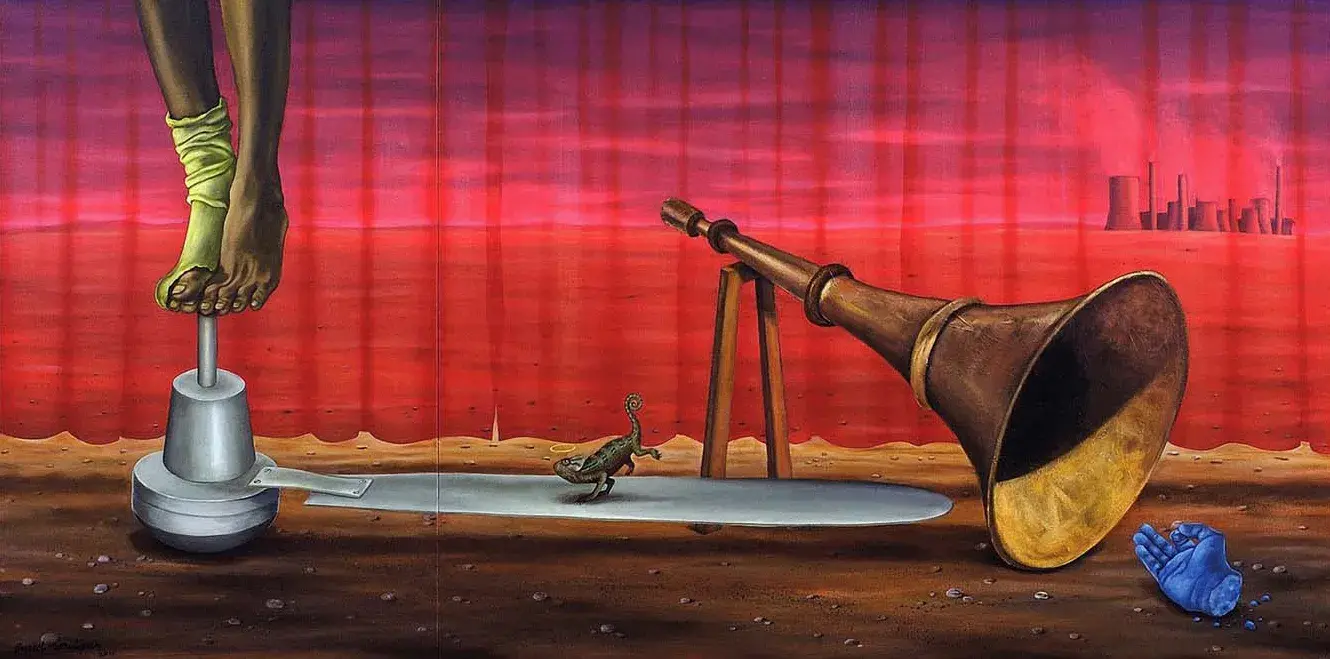

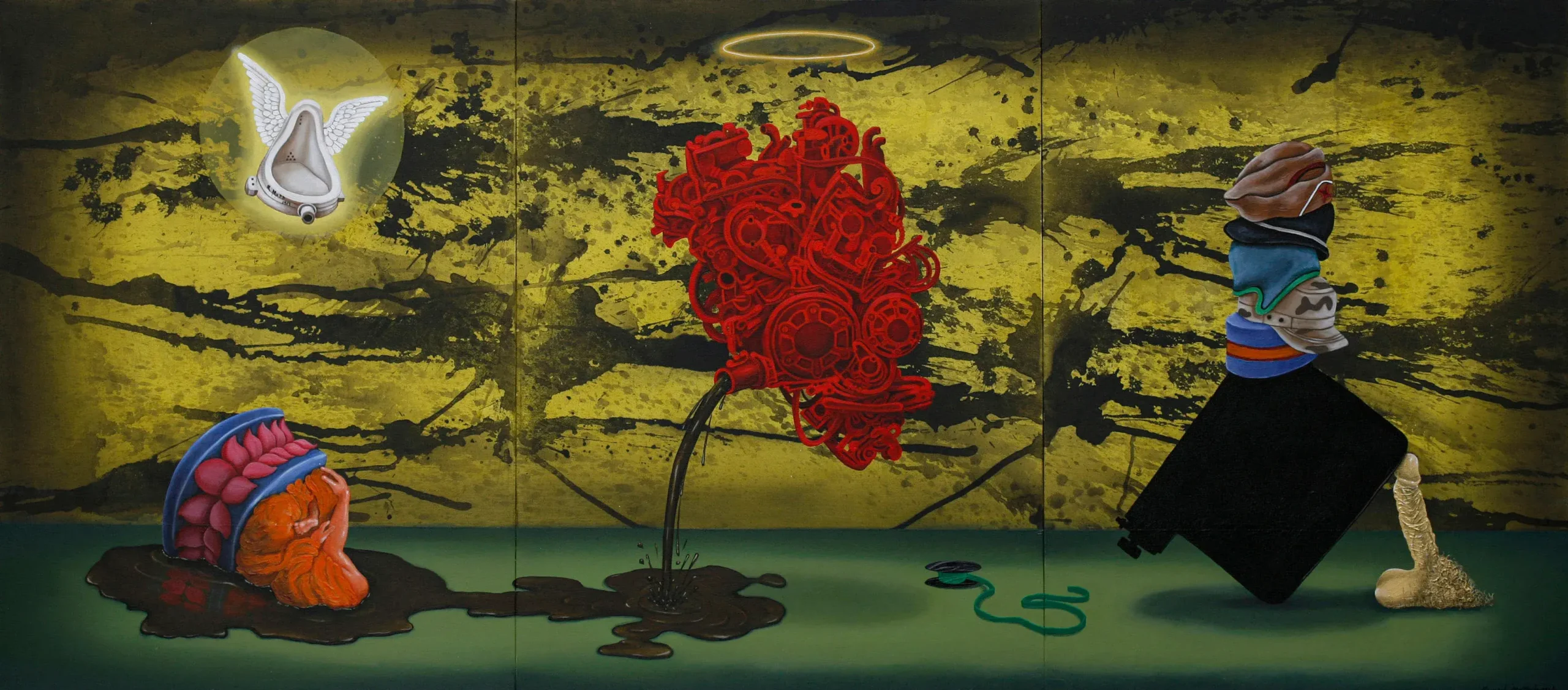

Suneel’s works, primarily built around an edgy Surrealist vocabulary with its associated shifts and substitutions of images and visual registers, are deeply concerned with the ethical dimensions of contemporary life. His vehicle of choice to stage the dilemmas that face Modern man is the fable, a genre that has had the capability to marry topicality with a populist and pedagogic aspect that can communicate to a wide spectrum of intelligence. His allegorical imagination is tied to an urgent moral imperative, and utilizes all the linguistic means that the genre puts at his disposal in order to uncover the iniquities that lie hidden beneath the codes that govern social life.

Many of his paintings are set in a theatrical space, populated by a cast of characters, – mountebanks, acrobats, freaks, man – animal hybrids, apparitions – that one would expect to encounter at a fairground, but could just as well have been displaced from the liminal, twilit world of a dream or a vision. The metamorphoses that these objects and figures are subject to, their extensions into other states and beings, their monstrous appendages, drive home the point that this is a world in flux, where identities are fluid and things are not what they seem, – a fact reinforced by the theatrical setting, itself a traditional and often used metaphor for the fickleness of appearances. The metaphor of the journey also figures prominently in his works. Many of these hybrids are in transit, going towards unknown destinations on unknown errands; – perhaps an echo of the passage from the interior to the city, and the nameless terrors that it holds?

The works exhibited in this show continue with the themes that he has been exploring for the last few years. The two paintings commonly titled “Festival of Narcissism” comprise a moralistic take on the role that self- interest plays in human affairs and its consequent perils. In both these works, the tail of the chief protagonist appears to be the crux of the issue, as it were; the tail is a common metonym for pride in mythology and folklore, often drawing upon its obviously phallic associations. One of these pictures, an ironic reversal of the celebrated HMV logo exemplifies the way he plays with images and genre. The covering of the dogs head in the paper bag and its mirroring in the phonograph horn evoke the insistent return of some guilt or shame that has been buried or left unsaid, the inability to come to terms with the self and the prodding of an unhappy conscience; the tail’s transformation into a ganglion-like structure, a burden, when seen in the context of its use in other works suggests that this work is an allegory of both vanity and remorse. Through such aesthetic maneuvers, Suneel’s works train a compassionate gaze upon our flawed humanity.

Sathyanand Mohan is an artist based in Baroda. He writes occasionally on the subject of contemporary Indian art.