Cognitive Dissonance

A Theatre of Disquiet

here have been many upheavals in the art world in the last decade or so; one development that has not received the attention it deserves has been the quiet, but no less significant assertion of what one could call a vernacular sensibility. This is the long view from the hinterlands of the subcontinent, looking in and existing at a tangent to the ‘mainstream’; it is the view of the outsider, yet one that embodies a distant promise of entitlement. The difference here is not an absolute one, but one of degree; – sharing many of the preoccupations that mark the mainstream and its metropolitan centers, yet existing at a slight remove from it, this unique subjectivity is grounded in unorthodox appropriations and parodic transformations of the languages and techniques that comprise the dominant aesthetic paradigms of the last century, often finding their equivalents within the mythopoetic spaces of local cultures. This tendency, while sharing an uneasy relationship with and drawing many of its linguistic and aesthetic moves from regional and local literatures, cannot, however be mapped onto it, – rather, one can find a generative instinct common to both. If one were to look at the originary conditions of this ‘school’ of art, it would inevitably have to take into account the slightly delayed, but no less disruptive (to traditional ways of life) arrival of the juggernaut of Modernity and ‘progress’, and the socio- political instabilities and fractures that it inevitably brings in its wake, – not always, it must be emphasized, in a negative sense ( for instance, the advent of Modernity and industrialization has often been able to successfully breach hitherto unbreakable class and caste boundaries, and have also provided outward mobility to subjugated classes seeking to escape oppressive social structures). Born of these experiences is a keen sense of the paradoxes of nationhood, of its difficult victories, of the peculiarities of its political class, and its ambivalent relationship to and invocation of a mythological/mythic space that existed ‘before’ and outside the teleology of history, existing as a symbolic realm of the possible.

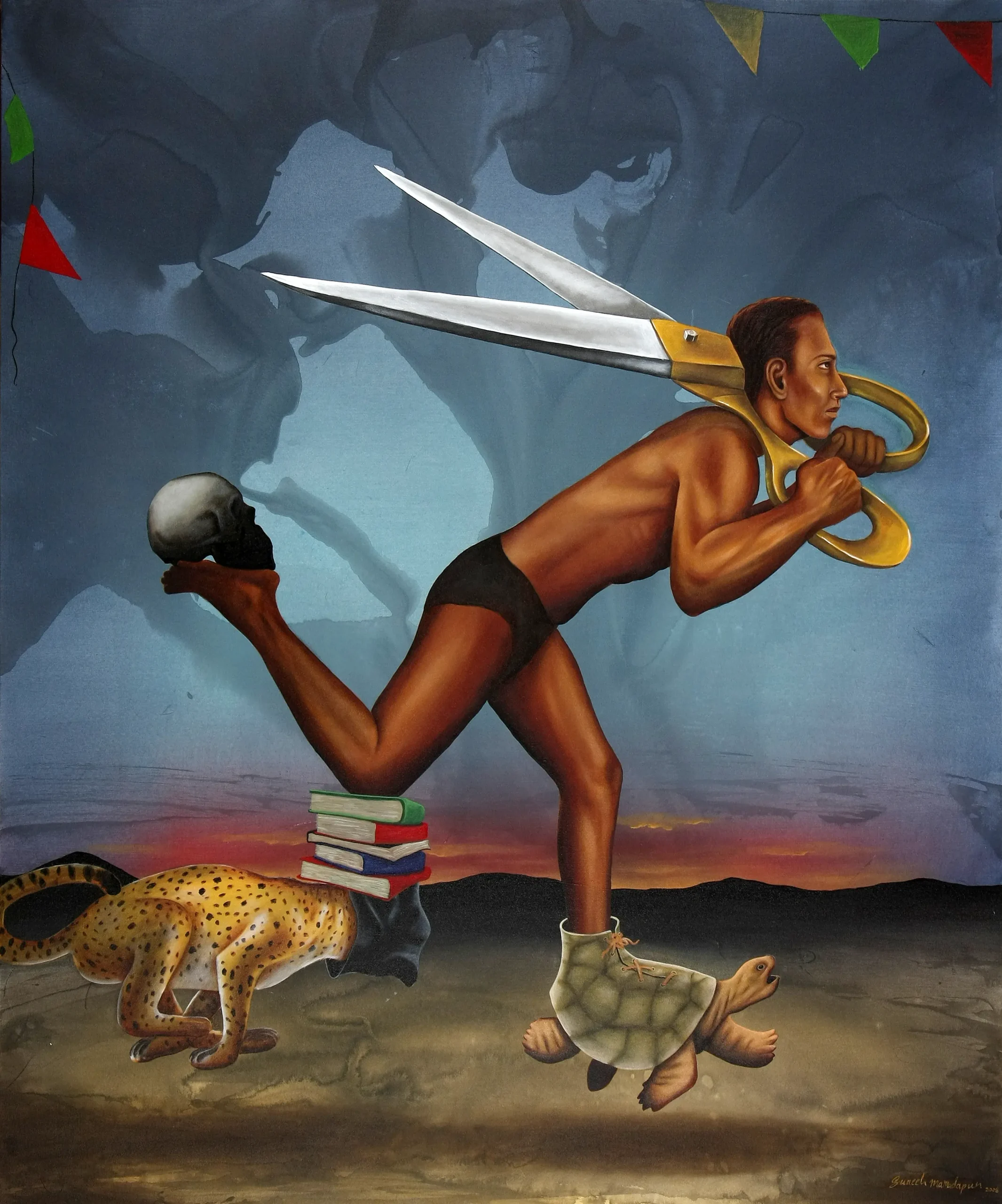

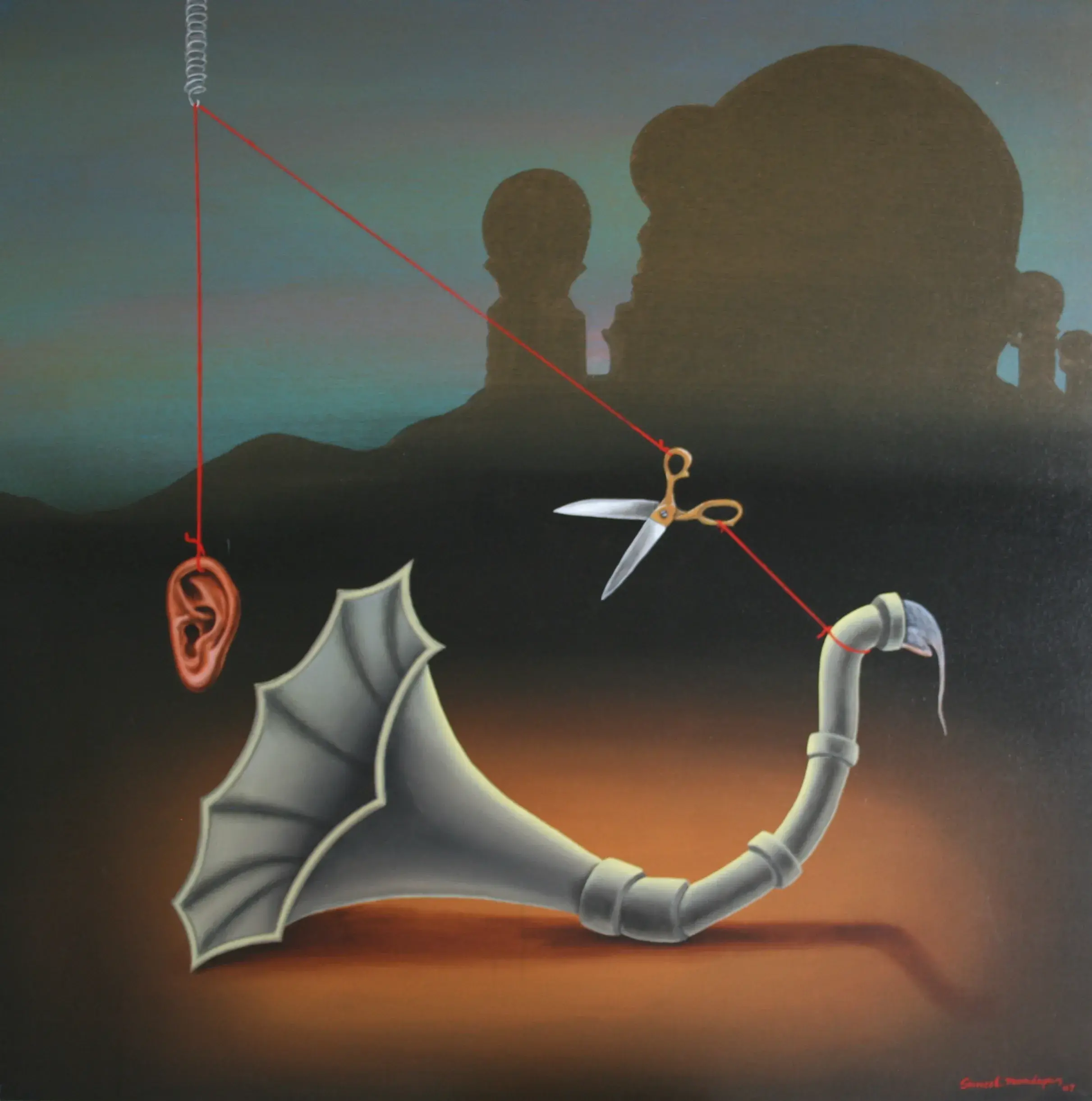

Suneel’s works, primarily built around an edgy Surrealist vocabulary with its associated shifts and substitutions of images and visual registers, are deeply concerned with the ethical dimensions of contemporary life. His vehicle of choice to stage the dilemmas that face Modern man is the fable, a genre that has had the capability to marry topicality with a populist and didactic aspect that can address a wider audience. His allegorical imagination is tied to an urgent moral imperative, and utilizes all the linguistic means that the genre puts at his disposal in order to uncover the iniquities that lie hidden beneath the codes that govern social life. The works resemble parables in their structural and linguistic organization, drawing upon the minutiae of everyday life which are often combined and recombined in surprising and unusual ways in order for it to be able to deliver its ‘message’ in as succinct and unmistakable a form as possible. Fables, however, by their nature are not wordy, requiring a rather stringent economy of means for it to be effective, and by that same token are not really fertile territory for ‘interpretation’. Suneel buttresses the possible weaknesses of his chosen method by significant recourse to the Modernist tradition, particularly in his mining of a rich vein of subversive humor that is central to many of its trajectories, one of the significant references here being the Theatre of the Absurd with which he shares an abiding interest in the potential of popular and outsider art forms, – vaudeville, the circus, and the shop of horrors, for example,- to destabilize established meanings and conventional power structures.

In keeping with their roots in the fable, the paintings abound in animal metaphors. These metaphors serve many functions within his visual world, often deployed in sufficiently humanized form in order to illustrate either the preponderance of baser human instincts by analogy, or in contrast the occasionally honorable function that reason, in its many institutional forms (as civic conscience, the law, ethics) plays in the regulation of our social world. The use of animal imagery is best exemplified in his painting titled “The Blue Monkey”. The thinker, that iconic image of reason reflecting upon itself, is here situated at the horizon of a landscape filled with a sense of uncertain dread, and that in its lack of definition invokes primeval chaos and primal impulses. The central image, thrown together in his unique fashion from odds and ends (the method itself suggesting extreme fragmentation and a patchwork of identities), potently conjures up a half-formed consciousness groping blindly about in the preternatural darkness, dramatizing the proximal relationship between reason and animality and the ways in which they mutually constitute one another, relaying it into the deeper, conflicted relationship between (what is considered) the ‘modern’ and the atavistic.

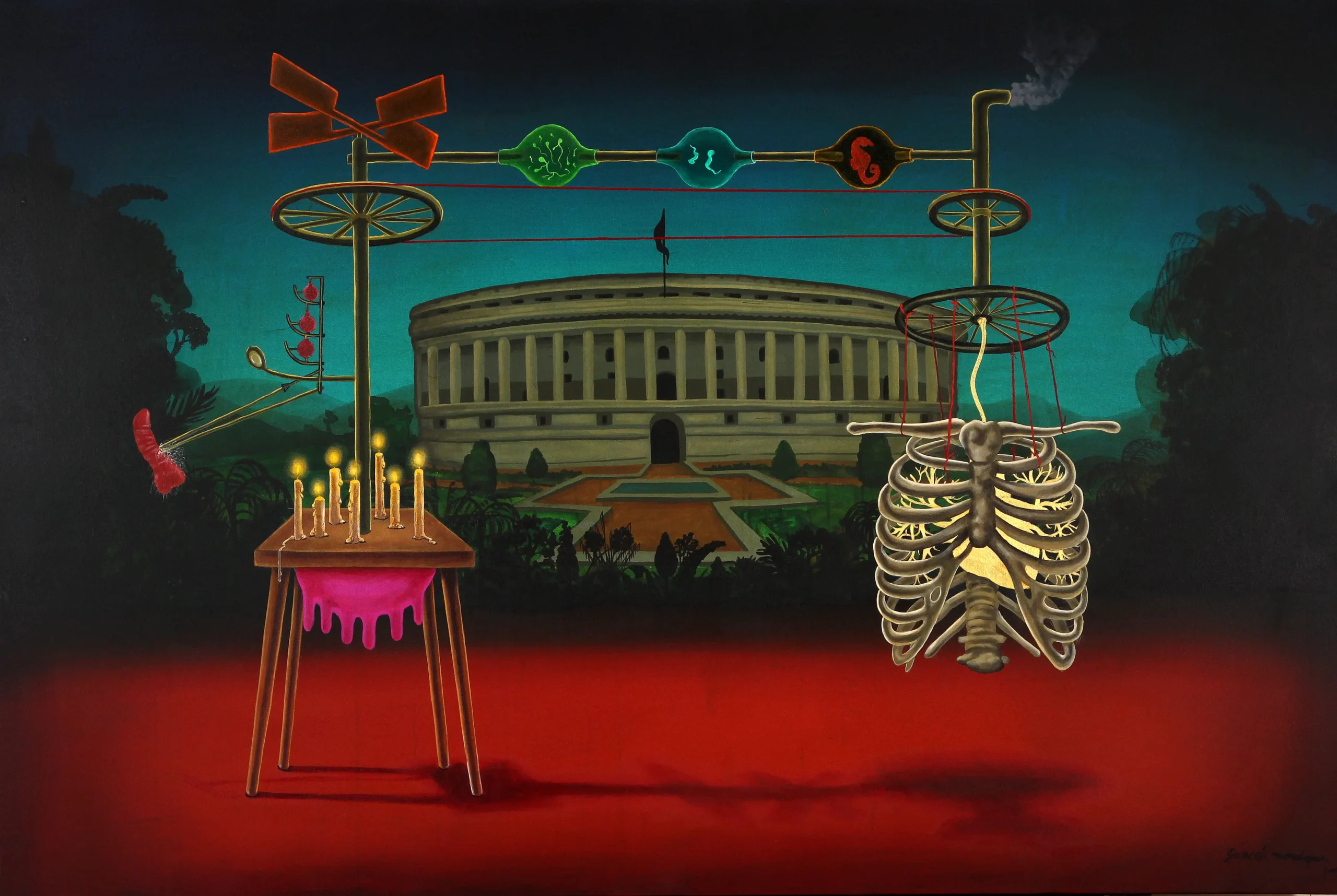

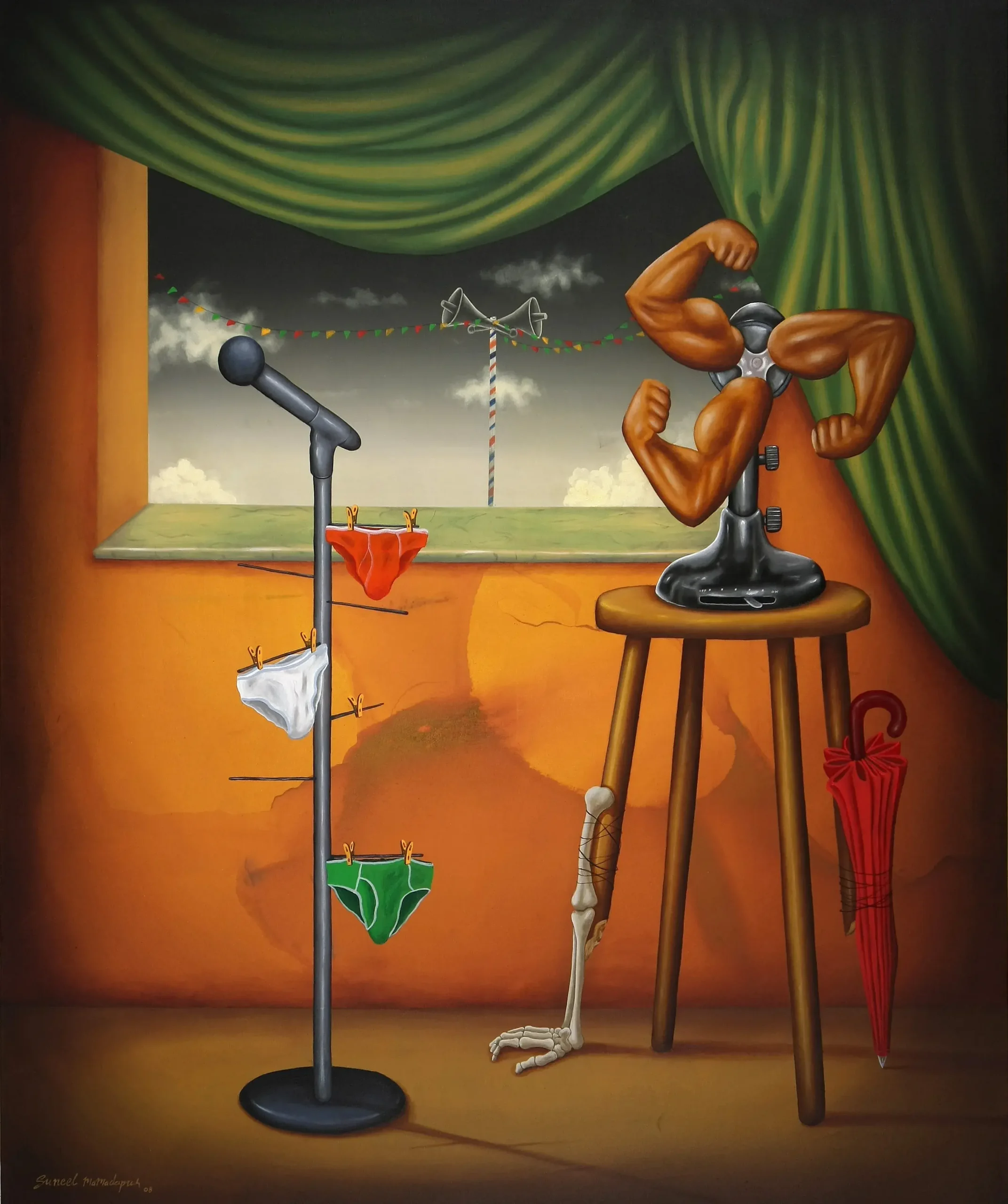

The painting titled “Colors of Fools Paradise-1” further exemplifies some of the unique features of his visual language. Set in a shallow theatrical space like many of his other paintings, what we have staged before us is a curious narrative cobbled together from a motley assortment of mundane artifacts and props, comprising a vicarious take on the state of our political landscape. It is an outsiders trenchant look at the vicissitudes of citizenship, and essays a deep rooted sense of disenchantment with the half-truths that constitute contemporary discourses of political emancipation. The microphone and the loudspeaker make up one of many such dialectical couplings/pairings within his visual universe, and is deployed in this instance primarily in order to critique the demagoguery and the duplicity of our political class, a fact further reinforced by the underwear that have been hung out to dry on the mouthpiece, which on closer inspection reveal the colors of the national flag, – a sarcastic allusion, perhaps, to the habit of our political class of airing their dirty laundry in public, as also to the way that the idea of the ‘national’ is itself routinely violated in the manifold uses that it is made to serve in this rhetoric. The trio of muscular arms that make up the blades of the fan further underline the machismo of much of this discourse, whose shaky foundations are propped up by a pair of unlikely bedfellows.

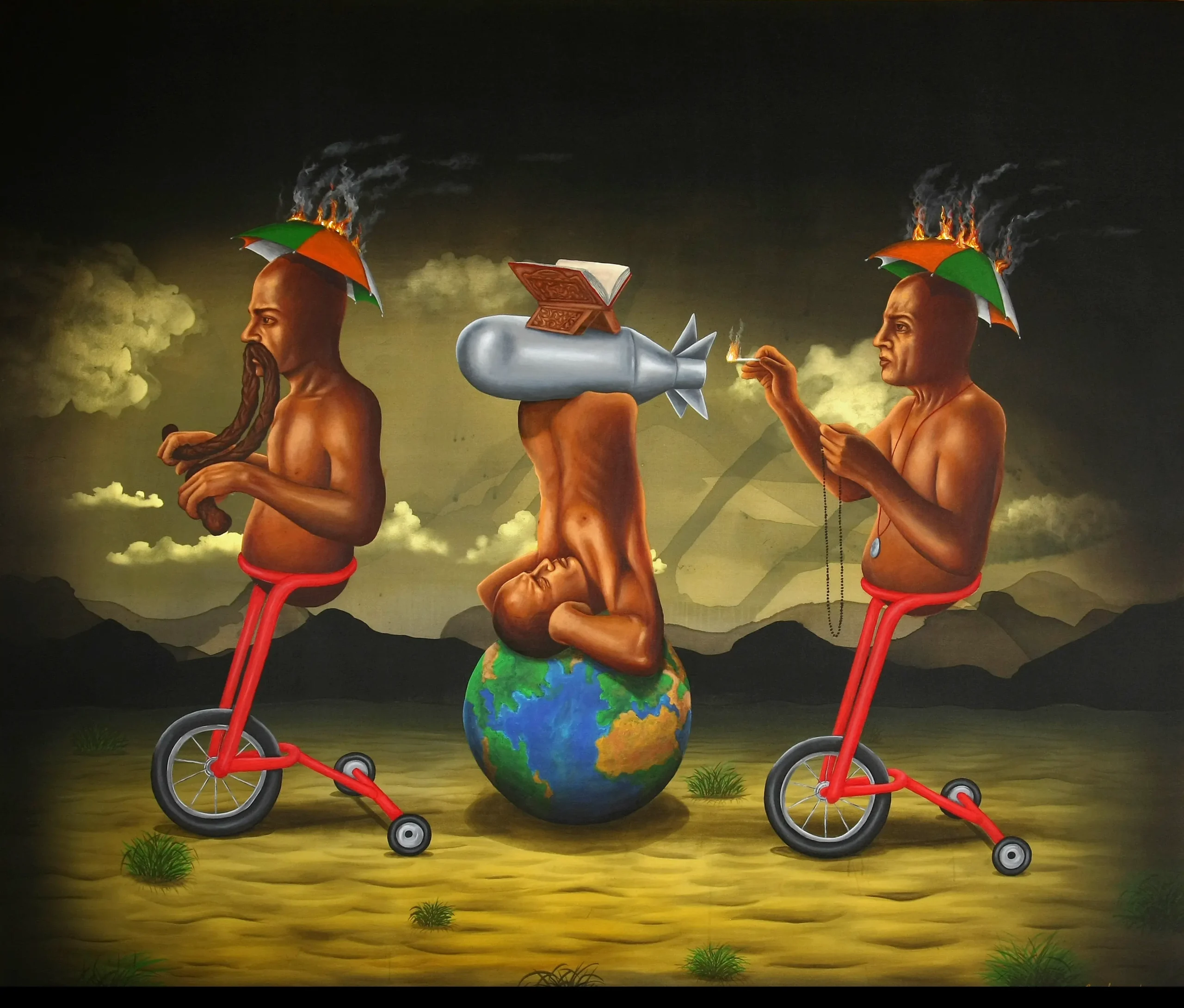

The critique of nationalism and its related discontents finds other forms as well, if one takes into account the many subtle references to it that are worked in through the backdoor as it were, and which often crop up in surprising places. The painting titled “Colors of Fools Paradise-2” is an extension of the earlier work and engages with the incestuous relationship between religious intolerance, nationalism and violence, and portray a group of crippled figures traversing the arena, perched on an assortment of ambulatory devices (including a globe). Set in his narrative space that has become a trademark of sorts, the work draws upon a variety of popular sources in its characterization of the rather dodgy trio, – visible particularly, for instance ,in the figure on the right, which evokes many stock features of the ‘corrupt priest’. The ‘national’ is invoked in the umbrella-shaped hats that the protagonists wear, a kind of headgear that one often sees at cricket matches (another venue of hyper-nationalist sentiment), which happens to be on fire here possibly due to the unbearable weight of the protagonist’s moral turpitude which appear to be considerable. There is also the suggestion that these figures that haunt his works are historical remnants of a kind, fated to replay without respite ancient errors and roles that have already outlived their purpose, but that nevertheless exist, clinging on tenaciously against their own obsolescence.

The theatrical use of space in his works is essentially a device to confine the action to the foreground, thereby concentrating it; backgrounds are usually rudimentary, often depicting, in a kind of visual shorthand a landscape that has been variously ruined and/or abandoned, giving the curious cast of characters that troop through its melancholy spaces the status of refugees from some awful catastrophe that has just taken place. The truncated figures and mutant life-forms that have lately begun to appear in his works reinforce this supposition, suggesting the disasters of war or a nuclear fallout, the images of which are everywhere with us, – and in its use of the fragmented body further locates him within a long politically engaged trajectory in art that includes among its exemplars Goya and Gericault . This re- presentation of what is essentially an already staged artifice has the effect of bracketing the action (the stage-curtains in this respect serving as a visual analogy/cue), evoking a lack of spatial and temporal continuity that translates into an overarching sense of disconnection with the landscape and by extension the metaphors that it usually stands for, – a sense of history, culture and belonging. These shattered physiognomies also suggest parallels with some of the more ‘marginal’ and eccentric cinematic traditions of the twentieth century, more particularly the Grand Guignol excesses of Tod Browning’s ‘Freaks’, as well as the work of that iconic auteur, Alejandro Jodorowsky, in the symbiotic couplings and transformations that these fragmented bodies are made to undertake/ undergo. All these traditions have an almost obsessive preoccupation with the psychic devastation implicit in the specter of extreme physical violence, but are also marked by an engagement with the ability of pain, as a limit experience, to be potentially transformatory and epiphanic.

Suneel’s works display a keen sensitivity to human frailty, , – which, in his moral and aesthetic universe awaits a rather incomplete kind of redemption, – and manages to delineate its essentially fallen state with both compassion and humor without falling into the twin traps of glibness or sentimentality. His works exhibit the kind of weariness that has seen too much of our baser selves for it to rely on easy solutions; while these works are often pitiless in their savaging of human folly, they nevertheless hold up a mirror to that aspect of our selves that we would try to forget, and in doing so, holds out the hope of recompense, of a kind.

Sathyanand Mohan is an artist living and working in Baroda. He writes occasionally on the subject of contemporary art.