Song of the Abandoned Road

Primal Power

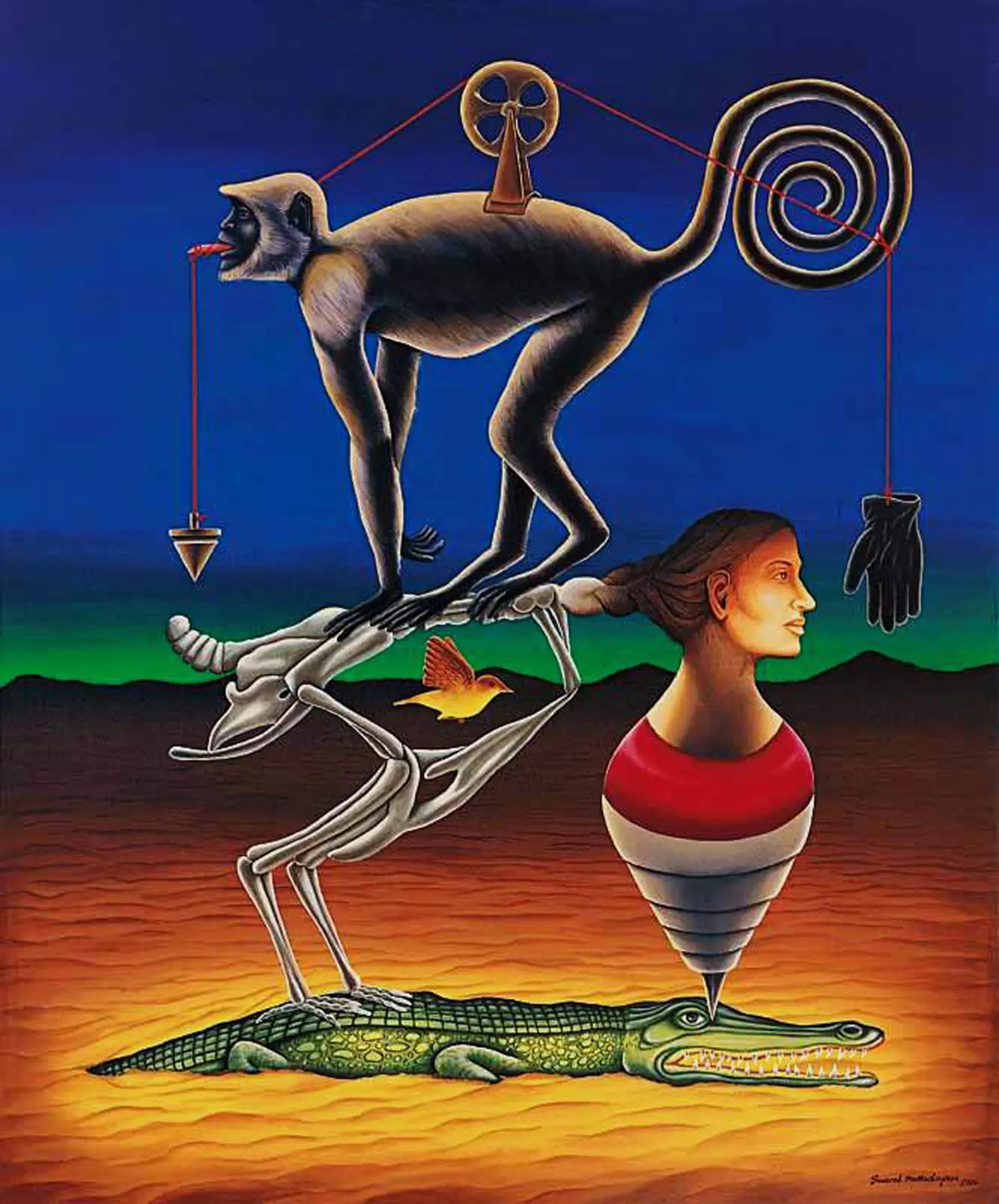

Think of a bittersweet, moving drama that preserves the vigour and the disquiet of modern day living. Think of realism bordering on surreal trajectory, which engulfs the wake of human intent and weaves the web of cruel selfishness, where man becomes God and manipulates all else for his own characteristic of consumerist consumption. This is the world of artist Suneel Mamadapur of Bangalore.

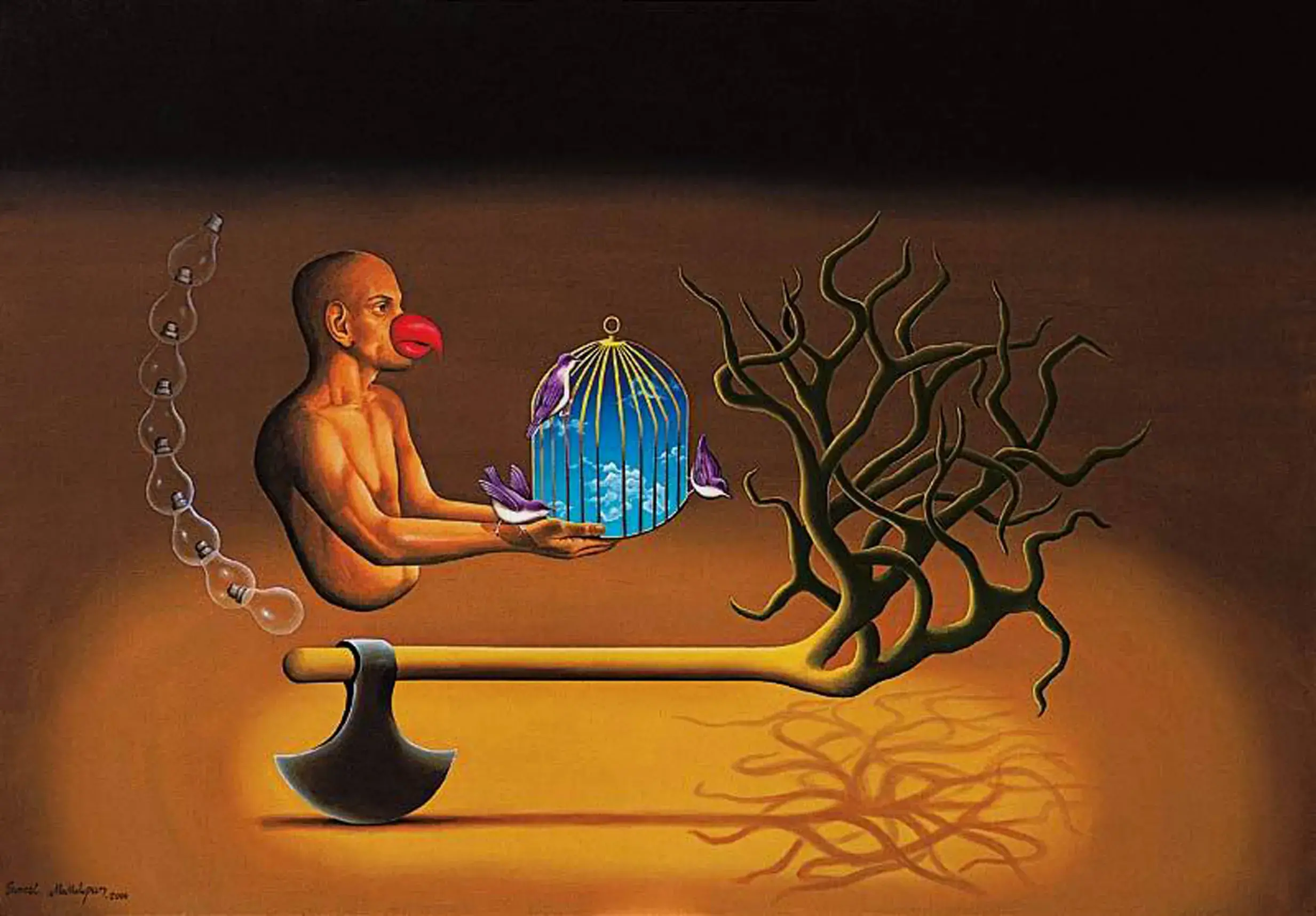

Personal history and the reality of the lived experience come together to personify the anatomy of angst and nostalgic regret in the works of Suneel who believes that art should be an autobiographical comment on societal hierarchies and pyramidal structures that reflect at best, social and gender inequities, political manipulation, religious violence and environmental degradation.

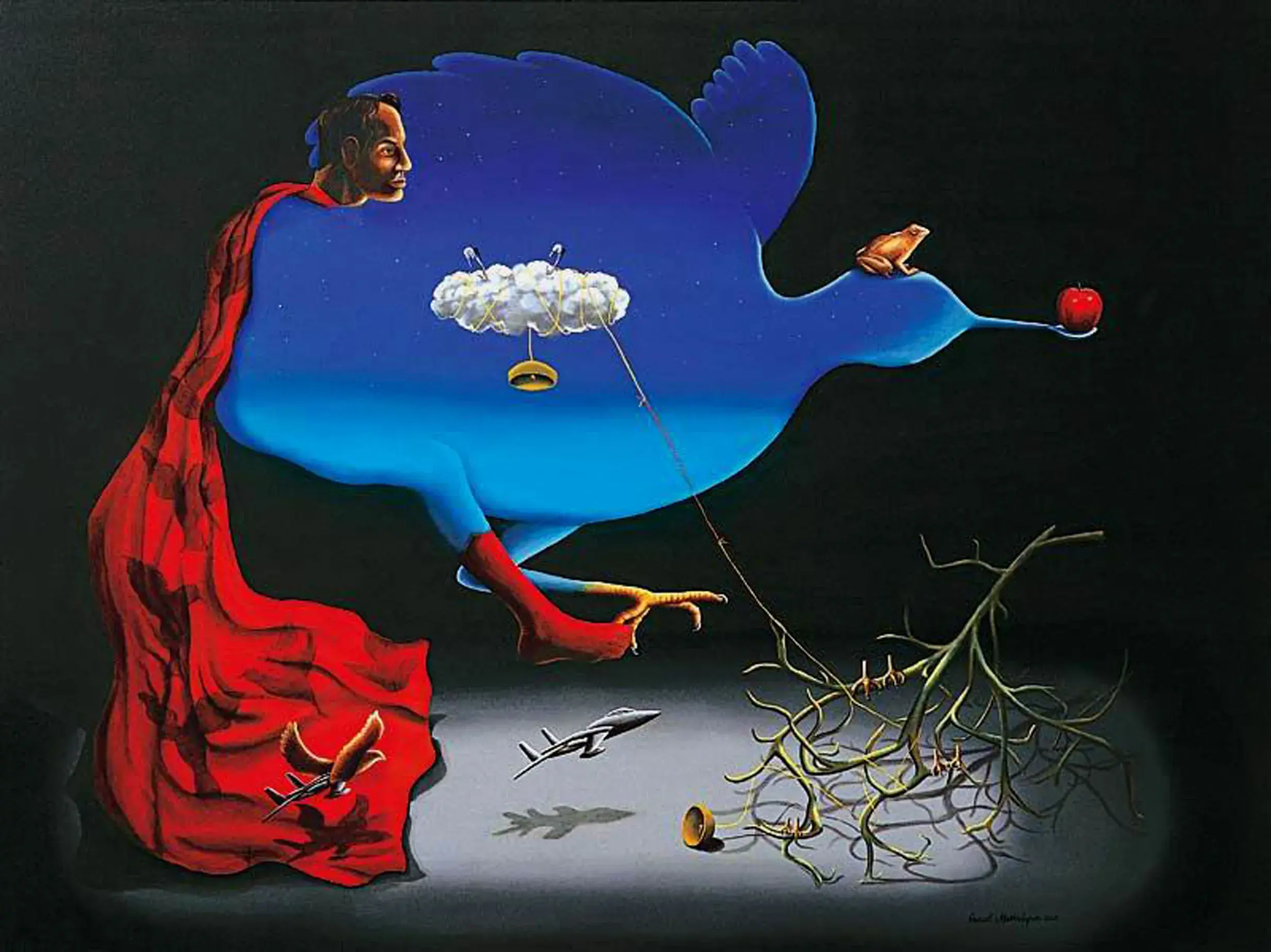

In his `Superman’ he gives us a hybridized image of bird and man being one.The blue bird fashioned more as a cloud with Superman at its tapered back , flies with a frog atop, and an apple at the tip of its beak, this work deals heavily in pivotal life events. In depicting the almost-cinematic episode, Suneel knows when to use naturalism and when to deploy theatricality (slow-motion, mime, paradoxical restraint, even an airplane and the thorny branches with surreal tones). The same unerring judgment guides the remarkable cast through the artist’s mix of colourative and exalted language; in particular, the contours have a way of making the dramatic poetic turns of phrase seem right at home next to plain talk.

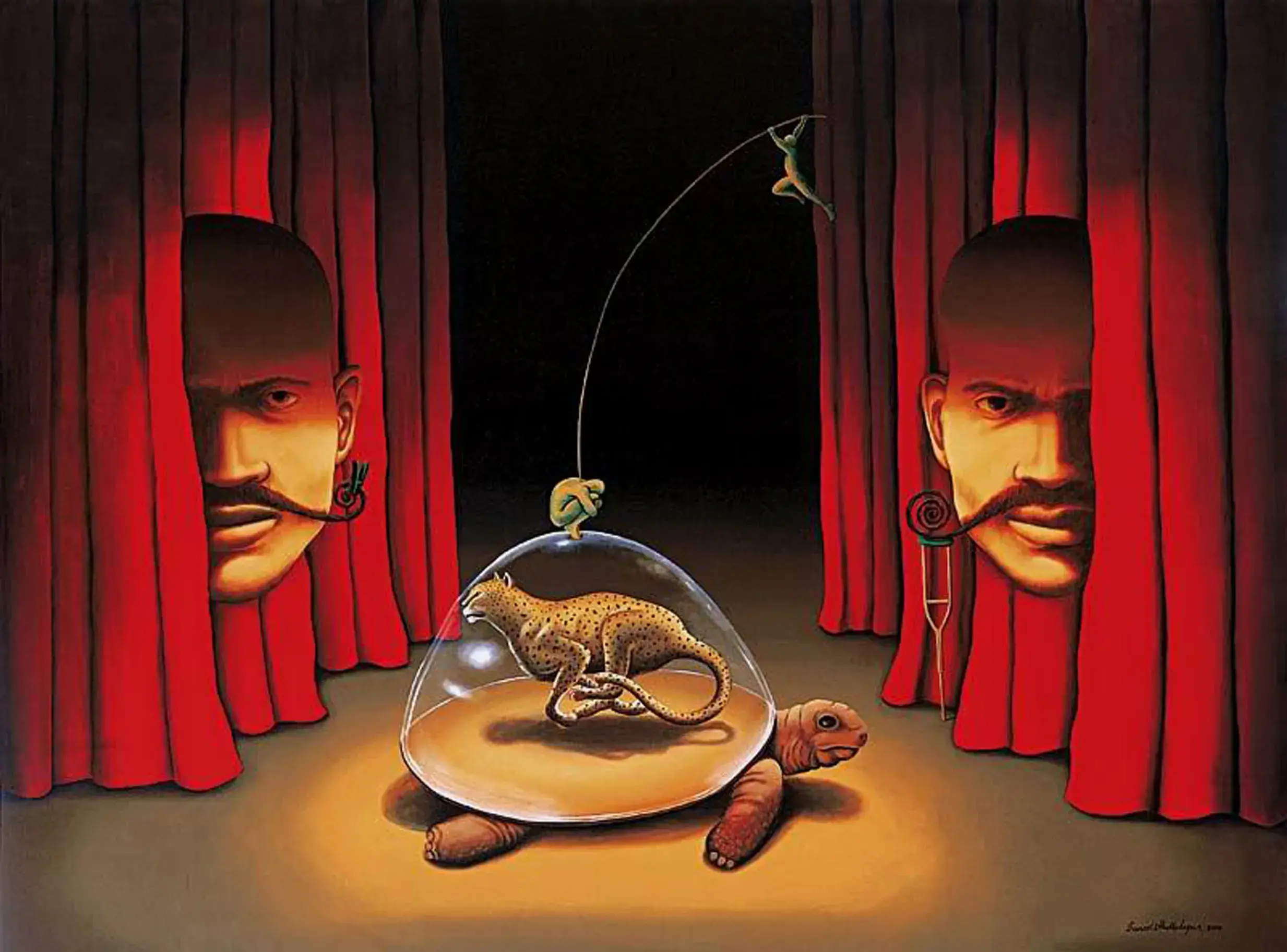

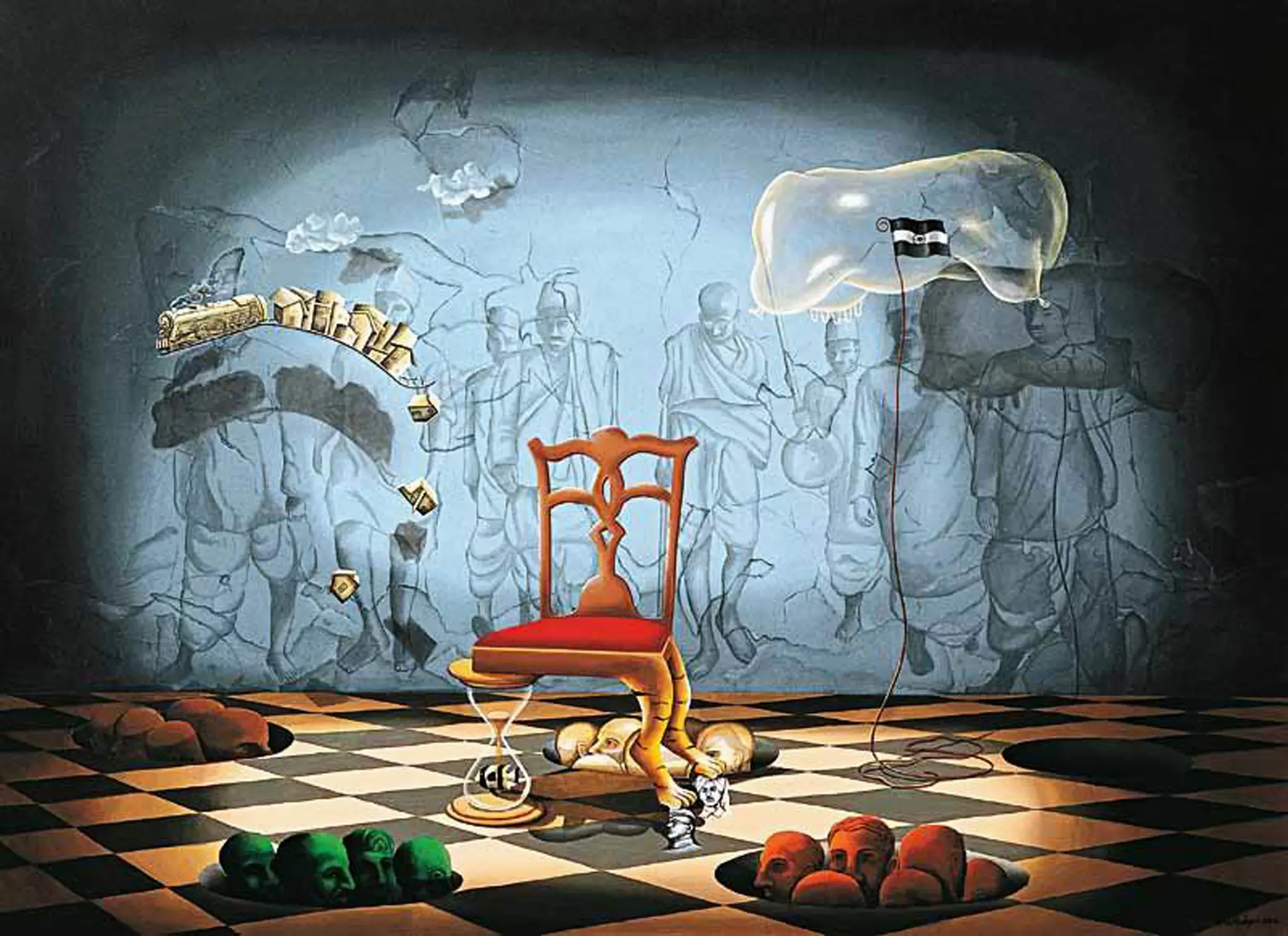

As a result, Suneel’s world comes vividly into being. And what a world it is — teeming with everything at once: pettiness alongside divine acts of kindness, goodness swirled together with aching cruelty, maybe a laugh followed by a kick to the gut.` Blowing in the Wind’ from the famed Dylan composition is a satirical comment on the fact that philosophies like Gandhism are passé.-this work is brilliant syncopation of a hard-edged, frosty feel with the transparent bubble like mushroom cover with the nubile nymph like maiden crouched in fear-the small bubbles, the elephant in the clouds and the image of one person on the side reflected with a throaty beauty that is impossible to resist, limps its way through a grueling yet changing world. Some people seem to have been born to suffer, but even for them, there is some crude mercy.The small baby is the projection of innocence and portrayal of Bob Marley on the curtain is a metaphor of the revolutionary while the bubbles are a portrayal of the sensitivity of life and the anxious insecurities.

`It is my personal comment on life.’ says Suneel. `We have Gandhiji’s philosophy, many singers including Bob Marley who always raised their voices against violence. But at the end of the day it seems that their thoughts and philosophy have nothing to do with our real life, those are confined to the pages of books or somewhere in a public statue , which is really pathetic. Stone hearted and selfish people create chaos and unending suffering.’

Quaint Renditions

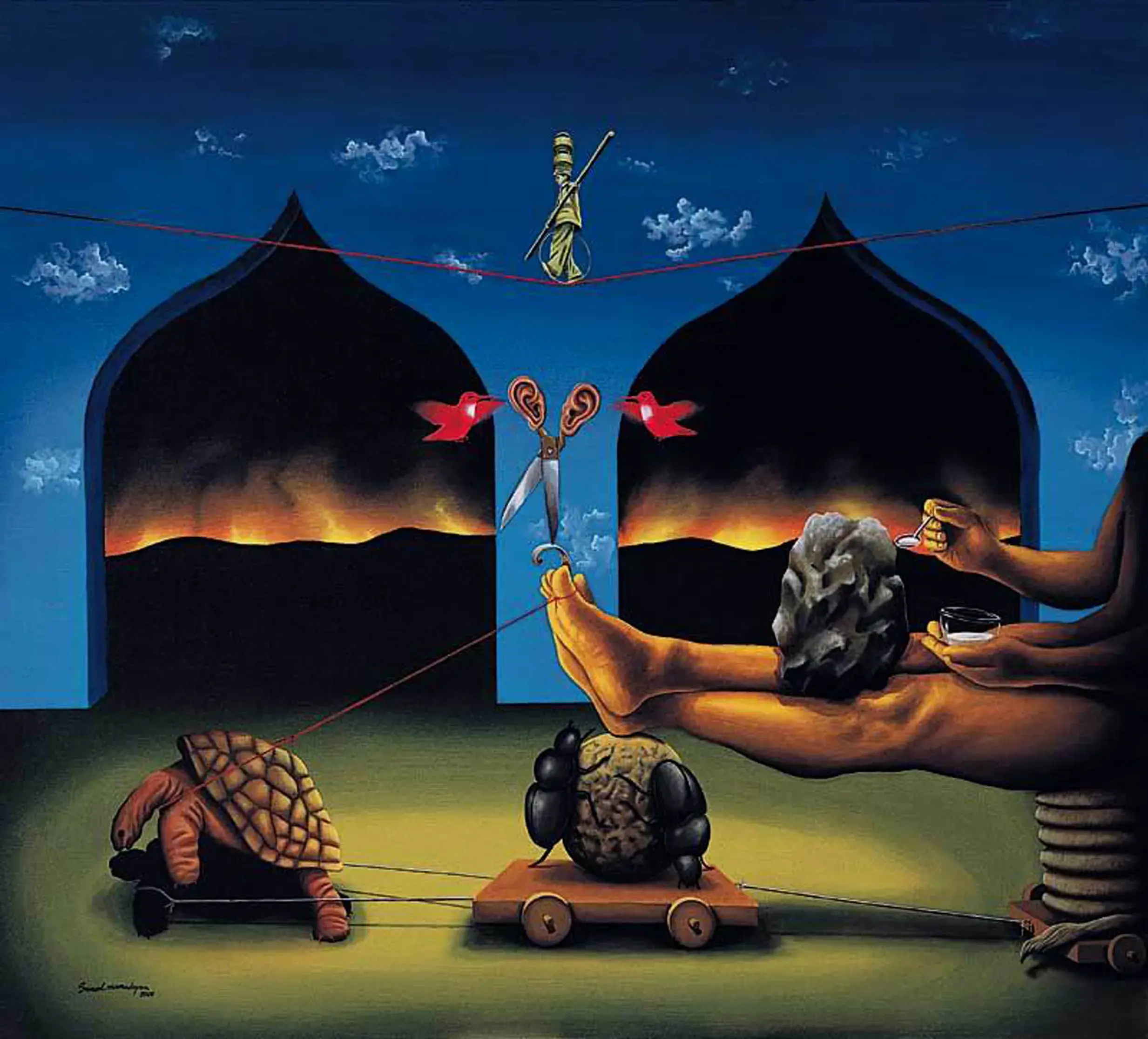

Certainly some of the paintings, have this Daliesque dalliance with surrealism of an otherworldly kind, which depict surreal scenarios in a raw style reminiscent of art brut, which also has a way of garnering reluctant praise.`United Colours of India’ is like a colourful treatise which must be commended for its originality. The use of the colours created in stark rendition of the skulls with the flag in the cloud is an attempt to impress the viewer with sophisticated technique. His naïve rendering of the nation’s freedom fighters is cunning, as well as quaint; it’s simply poignant for his strange and sometimes opaque narratives.

`I tried to capture some feelings of our country in one room. India, a colourful country with many castes, religions, cultures’ says Suneel`. People from all communities united together and they (our great freedom fighters) brought us a secured place. But now after so many years it seems that the place has become a mix of great imbalance, the word “unity” has got a different meaning now, everyone divides in the name of culture, religion, colour, caste. In such a situation, we once again need a Mahatma Gandhi, a Bhagat Singh, or a Subash Chandra Bose; otherwise once again somebody will rule over us.’

These paintings, however, linger in the mind. Suneel clearly believes in the epic, and also in the power of traditional painting to evoke it. Disconcertingly, he pursues certain traditional values of painting while jettisoning their every peripheral comfort, and commenting about societal mores in modern day living. The artist’s vocabulary of objects — airplanes, skulls, a space that speaks more like a temple, unidentifiable knickknacks — fill the work with chaotic portent. Why chopped-down branches of a tree near the blue flame-spewing bird in Superman? Literal meanings are left dangling, and potently bursting with satire, yet all hums with pictorial purpose. Delightfully darkened backgrounds in each work reflect the fact that Suneel is an adroit and forceful composer.

`God’s own People’ is a work that blends passion and panache. The two fingers that stand like the balance of life have betwixt them a fluorescent blue fist that has an equivocal tone about man’s role in the posterity of social instigations and intents. Blotchy beiges and vacantly electric blues establish, over the painting’s entire breadth, the weight of mounding earth beneath open sky and the role of the society that moulds and shapes a baby’s psyche, as shown by the infant’s feeding bottle and the large safety pin. Holding the entire scene aloft it is the safety pin that dots the air like an angry bee, while at one edge a battleship menaces as an inert intrusion of cerulean blue —in the small fist , to the extent, that is, that any two people sporting a giant ideology can threaten to bring down tradition, values ,relationships,et al.

As an illustration, the image is mesmerizing in its mettle of being manic, but as a painting, its powerful orchestration of forms lends it an acerbic gravity, even as its style almost defies us to take it seriously. Who would give a second thought to toy like objects, like a feeding bottle and a safety pin painted on a canvas and push-pinned to a wall?

`India has embraced all kinds of religion in her arms’ says Suneel. `Everyone is obsessed with their own religion, culture and nobody bothers about the country, and somewhere within this exists a kind of insecurity which results in communal violence. No religion teaches you the path of violence. It’s the people who are standing between the two religions who make the situation worse. This day by day creates a veil of insecurity within the country, religion and the most affected group of the society that is the common people.’

Critical Commentary

Other paintings feature the suggestion of practices that go back in history, `Rape in a Virgin Land’ has no female nudes, but strangely it actually makes you feel truly naked. Mostly smooth skinned and awkwardly poised, the parrot that lies in the canoe with two men flanking the canoe’s heads, is eclectic-the men are the vision of strength and muscle, they stare with blank, patient expressions. Even so, one senses the artist’s empathy for his subject, surpassed by only an urge to meet the demands of painting. With a quirkily honest eye, he makes palpable the vulnerability of the woman who is not there but she faces us, in the parrot that lies suggesting in a way that she lay helpless, elbows wide and fingertips joined in an indecipherable pose. Green in the parrot and its red beak speak of embellishment and feminine attributes. Overpainted contours, visible up close, show how hard the artist worked the composition to get the final position.

`Here I represented my critical thinking about our own culture’ says Suneel. ` We have a rich cultural heritage compared to the other parts of the world. Different cultures, and tradition, makes our country more colorful and beautiful, but in spite of all these our culture only makes so many boundaries for the people, and that too especially for ‘women’, it seems that as if they are always targeted for all the wrong reasons. She is the “Goddess” and she is the “Slave” there is no other relation in between!The skirt is the symbol of the young maiden.Right from that young age,she is the one who is vulnerable to all the actions of male domination. ’

In this painting, with the two bronze toned men clutching at the skirt that has been positioned like a table with an apple atop, the artist again convincingly locates forms, this time setting tawny earth tones beneath the dense glimmer of green-mud sea and a darkened sky. The great, unwinding mass of the figural skirt is bracketed effectively by two much smaller series of the transparent condom like creations each with an inbuilt inherent symbol, the first stands, a pillar of tart blue, while the second, seated one is a curl of livid pink. The feet of the dark figure nestle up against the skirt that actually also looks like a tiny temple, while a pale string of the necklace made of translucent symbols lie in the foreground. Like Bonnard, the artist seems to have dreamed his way to a climactic resolution, though with an utterly un-French gaucheness of technique. These images, too, have a peculiar gravitas of rhythm, even though their materials seem improvisational. The apple eaten off so crudely is indeed another element of the savage wrath and passion of man’s brute.

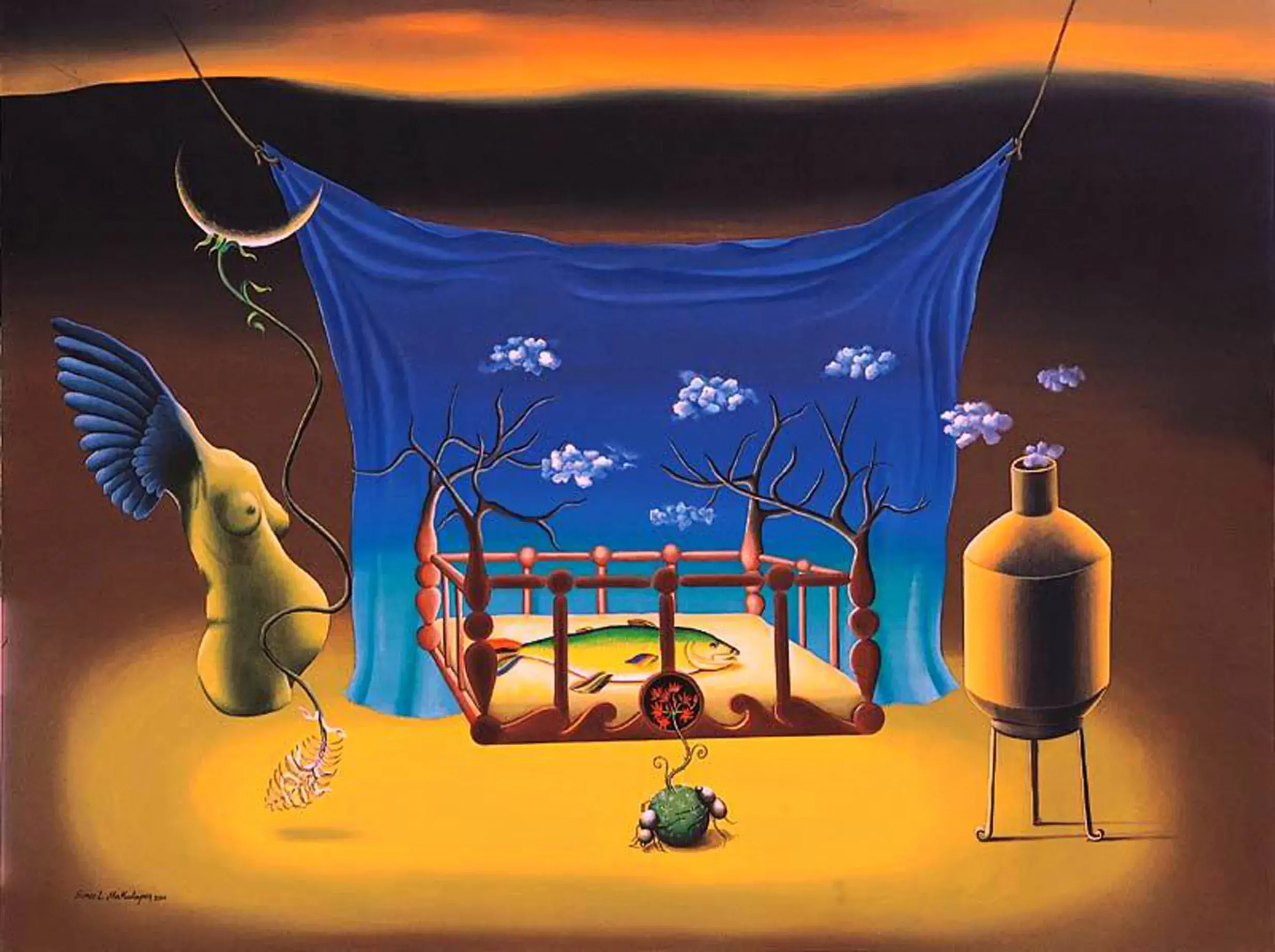

Most haunting of all is` A Layer of Moss Green’, which depicts a woman’s body curled in a pregnant mode but as a hybrid creature, and a fish lying in a cradle like cot with eyes open, a stream of bubbles emerge from the water heater used in old days without electricity .The curtain separates the child from the parents as Suneel personifies their one room livelihood Colors give the scene a resonant dimensionality, vividly conveying the artist’s illumination in a twilight zone with the curtain and the elements that lie all around. The woman’s predicament is spot on while with the fish and the cradle it seems as if the artist were entrusting the meaning of the scene to a higher power, possibly the “collective unconsciousness”. One imagines that, having performed the artist’s duty of constructing a scenario, he shares with the viewer its mysterious possibilities instead of wrapping it in insinuations.

Of course, Suneel’s romantic faith in the transcendent manifests itself in the most unsentimental of styles. His memorable paintings seem to be a soulful defiance of both a critic’s categories and an academician’s techniques. They have the mordant tenderness of an artist who can’t shake the anxieties of the nuclear age, yet chooses to disregard its “-isms.”

`This work is very close to my heart’ says Suneel.` Though the work is entirely my personal experience, one can easily relate it to their own feelings. Here I have fantasized some truths of my life, which is my mother and father’s relationship, their romantic life far from the city, the way they carry their small world with the little that they had. My childhood was a struggling period for my parents, when we had only one small room. A room, divided by a curtain. One side of the curtain is the romantic world for a couple and other part a fantasy world of a child, which I represent with a curtain like sky. The two images of a pregnant lady and a manual water heater represents a romantic life of my parents and also their struggling moments.The water heater is my father,the clouds that billow out are what will drop as rain for the fish to survive.It is my comment on the daily struggle of rural people who have to provide for their families come what may.The fish lies in wait for water to fall as raindrops,that is the sustenance. ’

Suneel also zooms out to expose a wider frame with new details and removes the romantic element he speaks of to give us visual allegories.

Rewriting Modernism

The primary challenge for representational painting today is creating work that does not feel anachronistic. Modernism rewrote the rules of art, and if you’re not careful, realistic illusionism can be dismissed as old-fashioned. Some artists are self-consciously traditionalist. But those who want to be part of the contemporary discourse have been forced to adopt various “modernizing” strategies: They may add conceptual layers to their painting, strive for photo-realism, incorporate the lessons of abstraction, or adopt poses of postmodern irony. Another strategy is to confront the past head-on by directly referencing art history. Always bold, this move can also be deceptive. Why? Simply because the past’s legacy is weighty, and it can either inspire or overwhelm an artist, as a comparison between these works demonstrate.

What excites and entices the critic is Suneel’s subversion of reality even as he laces it with satire. The images in the show are rendered in multi-point perspective, a complex technique of almost scientific precision that most art students cannot master because it’s not easy to produce competent, intelligent illusionism. But Suneel has filled the center of his compositions, where the vanishing point would be, with an inkling of ideas that go beyond an easel, which improbably leans forward, defying gravity as well as the carefully orchestrated overall perspective. By examining distinctions between art and science, and the significance of following and breaking rules in the creative process, Suneel’s quasi-appropriation traces the elusive divide between painting that is genius and painting that is gently meant to draw you into the vortex of sociological symptoms.

The images in the works are often like cryptic clues, which assist as well as exemplify a commentary that is satiric and help one to decode the invested meaning that is disguised through oblique and elaborate devices of representation. Suneel in this way offers an alternative visual strategy for commentary, one that appears to link with an older visual and cultural tradition but one that ends up using that evocation like a well-laid red herring.

An admirer of Bhupen Khakar, Surendran Nair as well as Anju Dodiya – his urge is to ,move away from the generic and move towards classic satire, and make somewhat covert criticism of the nature of society and politics, human lust in the face of female naiveté and vanity in an age of conspicuous consumerism. He interjects heavily with text moving from the visual to the contextual- political to the polemical.

`I explore the ideas of identity and subversion in relation with contemporary pratices and tradition, from an autobiographical as well as critical perspective, and it is this that has been the central focus to my work over the last two years. The nature of my work is complex and references for me are all rooted in the orientation of what is observed in daily practice. Myth and memory are simultaneous for me , folklore and classical rituals and traditional practices, historical leanings and politics coupled with the experiences of my own life become the exploration of enquiry to the works within this exhibition.’

The drama of intent turns into a theatrical device,and colour then is used to sharpen the contours of the images;what unravels is the corollary of the contextual powers that drive what is within and without.Interestingly in any sub context the equivocal tenor is lithe and lives out a singular throbbing; within the skin of the inner terrain they carry the outer,the diabolical diatribe of life is what they find themselves in;the artist also naturally tries to accentuate the tenor of whatever issues they address. In doing so we see that there is a consistent sense of rhetoric; a constant play of tensions and tangential counteractions that arise between the idealized and the real-and what gets highlighted is the process of the unfolding debate of all the little things we have sacrificed at the altar of selfishness and wanton greed.

No two works in this historic unveiling are similar. The collection which celebrates the inertness of allegorical imprints deserving of the name pares itself down not in the pursuit of style points but in an effort to frame the relationship between man’s nature and man’s belief, between the magic of solid and void, between the catharsis of nature and culture, and the celebration of colour and its dense depth — to explore how the eye sees and the mind understands those differences when an artist translates the mind’s message with taste and an intangible prowess. Life’s spectrum in the hands of an adroit artist can pull off stunning visual echoes and therein lays the strength of this felicitous blend of the old and the new.

UMA NAIR