Desert of the Present

“Think, dear Sir, of the world that you carry inside you, and call this thinking whatever you want to: a remembering of your own childhood or a yearning toward a future of your own – only be attentive to what is arising within you, and place that above everything you perceive around you. What is happening in your innermost self is worthy of your entire love; somehow you must find a way to work at it, and not lose too much time or too much courage in clarifying your attitude toward people”.

– Rainer Maria Rilke: Letters to a Young Poet (1903) [1]

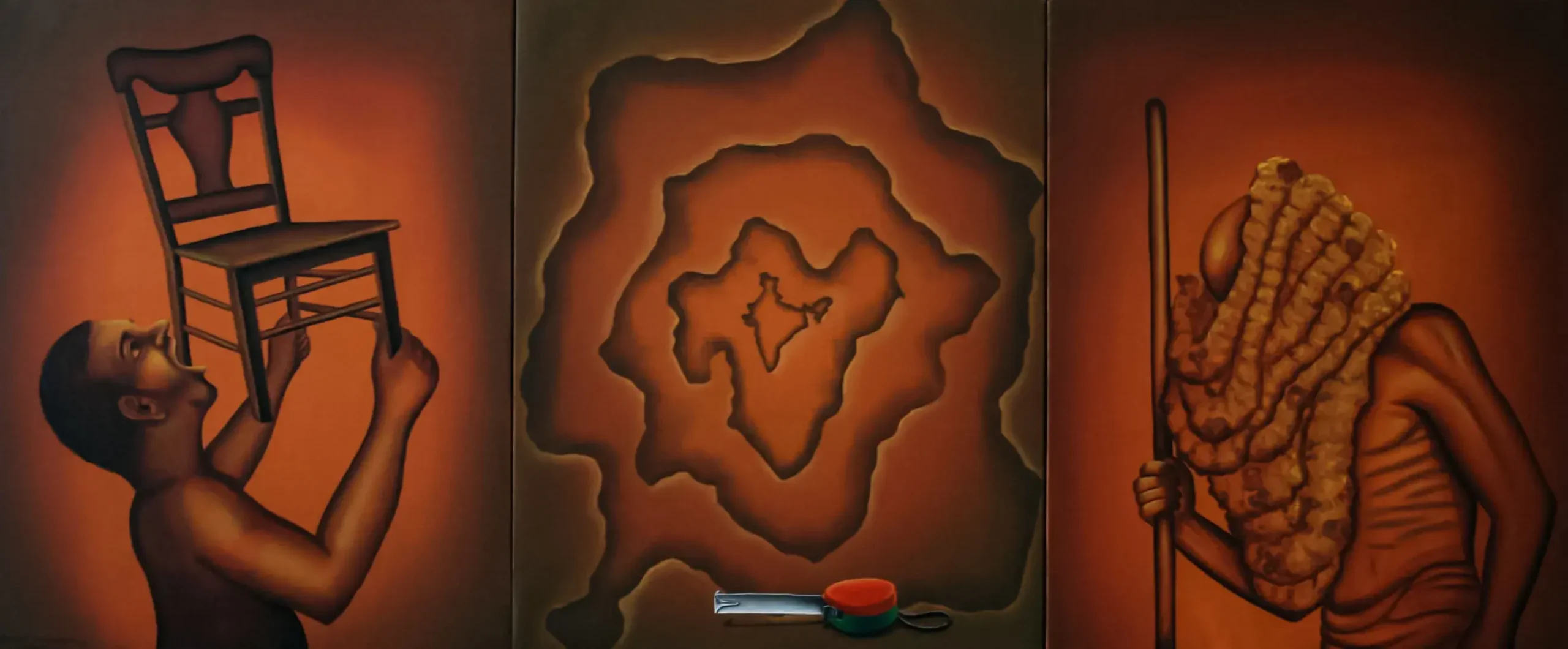

Suneel Mamadapur’s paintings seize the eye at once. They take the form of precarious tableaux, as the artist builds up elaborate assemblages of humans, animals, ghosts, trees, architectural elements, and a variety of mechanical contraptions geared to the mandates of balance, purification, mobility and communication. Except that the balance is usually threatened, the purification subject to contamination, the mobility curtailed and the communication impaired. Mamadapur’s protagonists are caught up in improbable scenarios, playing roles that condemn them to instability, hazard and suspended animation. They inhabit the desert of the present, complete with metropolitan backdrops that belong at once to New York, Bombay and Gotham City. Like characters in a Beckett play, they pursue a carousel of mirages and hallucinations, unable to rewrite the script or exit the stage.

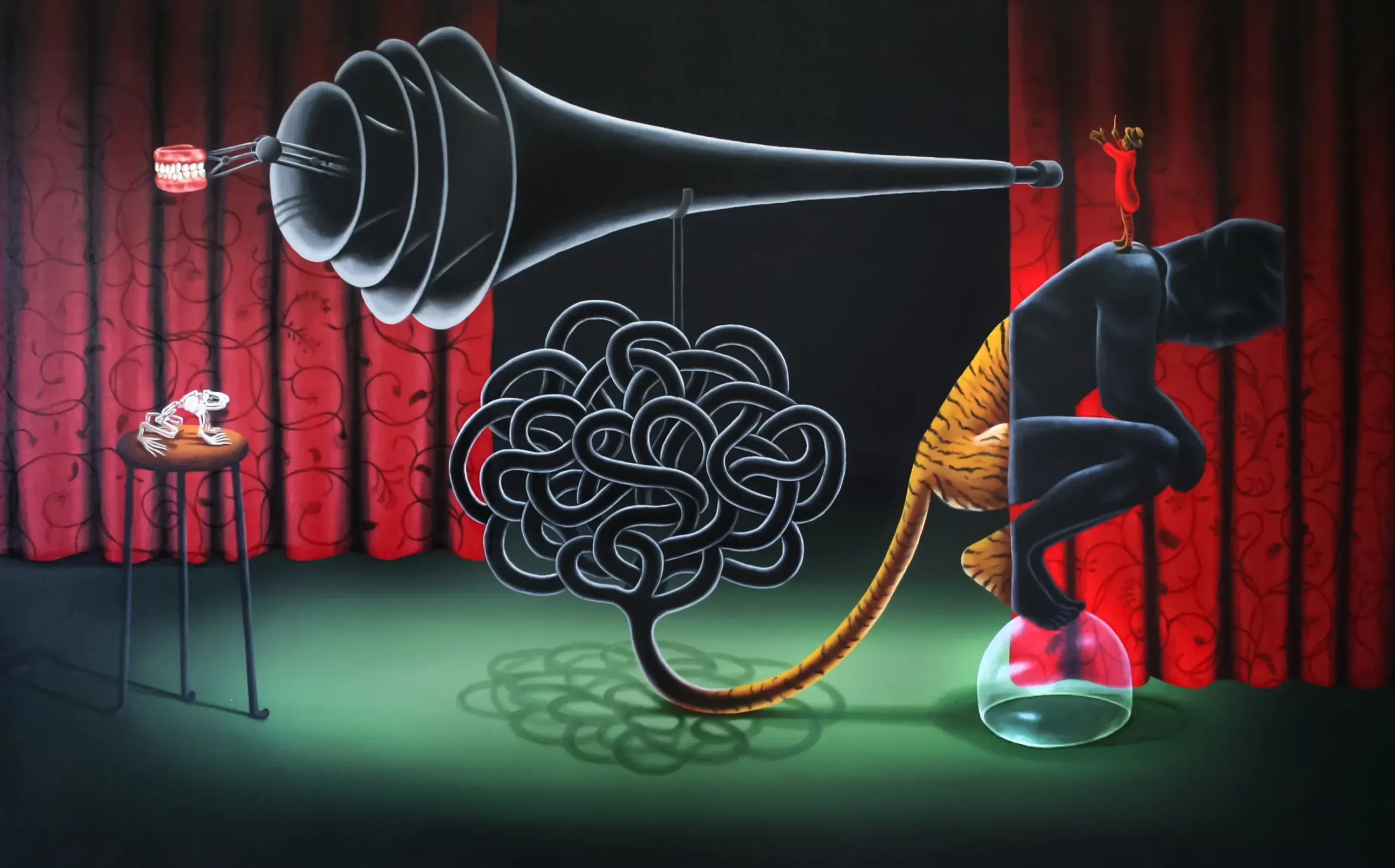

Viewers may be forgiven for being reminded, on first acquaintance with this young painter’s work, of the circus, the magic show, the freak parade or the museum of curiosities: a ‘Believe It or Not’ air hangs over these meticulously conceived and detailed paintings. On looking closely, however, we find that his contraptions are held together by delicate and complicated interrelationships. In ‘Untitled Play’, an acrobat, part man and part tiger, balances on an upturned glass bowl. He stares into the darkness offstage while a miniscule orator stands on his shoulders, gesticulating into a bullhorn with many corollas. A set of dentures extends from this daunting device in a frozen smile. A frog skeleton crouches on a tripod, an attentive fossil offering a counterpoint to the miniature demagogue. The acrobat’s tail, we now see, has grown into a tangled nerve-tree. These images of arrested motion, the tyranny of time, and the gap between intention and execution seem theatrical to begin with; but they claim our interest, exert a haunting force.

A boat goes absolutely nowhere in ‘The Third Child’. Its solitary occupant is a figure that is dripping away, its consistency between those of wax and ectoplasm. Two other figures, resembling oarsmen, turn out to be torsos fixed into tripods: they stand outside the boat, making gestures of propulsion all the same. One wears a bag-like mask, the other’s head is a wire armature. Above and behind these pilgrims of stasis and oblivion (the boat, a parody of Charon’s, carries its own water on its dry voyage, dripping some from a tap set below its prow), a funambulist makes a perilous crossing, carrying an elephant across a tightrope strung up between two blocks of a ruined colonnade.

The funambulist reappears in ‘Metro Fallacy’ as a bearer of multiple burdens: he carries the elephant on his back; but has no legs in this version, and so moves slowly on crutches that end in elephant feet. He follows a skeleton and pulls in his wake and a wheeled tortoise carrying a brain on its carapace. This bizarre yet curiosly stately procession has its own mobile backdrop: an ornamental sky that two anonymous figures carry along the promenade, a screen that shuts out the grey bay with its Life of Pi tiger on a boat. Who are these figures, and what are they doing? Are they captives of a broken past, negotiating a desiccated tradition? Or are they, to invoke an image from the divan of the inimitable Ghalib, spelling mistakes that someone forgot to erase from the slate of history?

The crouching fisherman who occupies one half of the diptych-style painting, ‘Deleting Sky’, extends his fishing rod into the opposite half of the frame, which is a duneland; while his habitat is the sea off a metropolis and his mount a half-drowned elephant, his rod seeks a fish swimming in a bowl that dangles from a plank, on which is seated an Einstein in miniature. As our eyes travel across the painting, we find that the Einstein-bearing plank is a seesaw whose other end rests on the fisherman’s head. Mamadapur delights in orchestrating a choreography of checks and balances, vectors and scalars, possibilities and impediments, deceptive hopes and missed opportunities. Much in these interlocking arrangements suggests the operation of karma and maya, moral mechanisms that thrive on the play between effort and outcome, insight and delusion. The ‘Believe It or Not’ air of these paintings is sustained by a philosophical regard for actions and their consequences, desires and their fruits.

I am intrigued by what Mamadapur has set out to do. I am sympathetic to his metaphor-making impulses and the predicaments into which he so richly imagines his protagonists. I respond with warmth to his intense preoccupation with generating a mythology for the human subject whose destiny it is, to wrest pattern and significance from the unpredictable and multi-layered Now. At the same time, I am worried that his art partakes, to some degree, of two widely prevalent house styles of contemporary Indian art: the first being the drift towards whimsical, fabular allegorical figuration that owes as much to the Kerala temple mural as to the Tamil movie poster and Hieronymus Bosch; and the second being the “new mediatic realism”, as Nancy Adajania has problematised the phenomenon in a much-remarked critical essay devoted to the shifts in the historic relationship between painting and the mass media in India.

Put these treatments together, as many young Indian artists do, and all the skies are screens, much of the mise en scene is cut-and-paste, the eclectic but randomly assorted archive holds everything from punk Gothic and Boris Vallejo to Dali and Clemente, and PhotoShop provides the new cosmogony. When the use of witty, erudite art- historical references runs berserk, we find ourselves weighed down by the telephone directory of world art. These are hazards that Mamadapur must remain aware of, even while he explores the intricate tapestry of dreams, nightmares and dilemmas from which he culls his images.

I have been looking closely, for a number of years, at the manner in which an artist is socialised as an artist in India: how he identifies art as his vocation, how he prepares himself for it and enters into the institutional structure of the art world; how he develops his notion of a style, an exploration of concerns, a career, and success. Phrased as this journey of self-making is, within the studio-gallery-auction house circuit, it tends to be biased heavily towards the attainment of a comfortable insiderhood. The young artist acquires the habits of rhetoric and presentation practised by the successful exemplars he idolises; he identifies the approaches best received by the art economy and rehearses them, veining them with personal variations as he goes along.

This imbibing of received notions about art, artists and audiences has two orders of effect. The weaker sort of young artist ends up with a generic pictorial language patched together from unexamined preferences and references: he becomes the picture of the intention to succeed, a draft of insiderhood that never quite makes it to the finished picture. The stronger sort of young artist works his way through rawness and anxiety; he survives the ambush of the given, integrates what he has learned from this encounter into his ongoing explorations, and continues to address the minds and bodies of individuals, their evolving relations with society, history, nature and technology; he becomes an insider who can alter the state of the art world.

Where the weak artist traps himself in a welter of bafflements, the strong one formulates and tests out an architecture of selfhood. He internalises Rilke’s marvellous advice to the nineteen-year-old poet who wrote to him for guidance (Rilke was twenty-eight, already celebrated, going through one of the great creative turning points of his life), and which I quote in the epigraph to the present essay: “What is happening in your innermost self is worthy of your entire love; somehow you must find a way to work at it, and not lose too much time or too much courage in clarifying your attitude toward people”.

Suneel Mamadapur holds considerable promise: he has a hunger for images that express what is happening in his innermost self; he has a passion for making those images carry significant meanings beyond his private experience; and he has a need to communicate his preoccupations to an audience in ways that are magical rather than banal, compelling rather than didactic. I am certain that, in the years to come, he will put himself through the refiner’s fire, grow out of his love of excessive detail, hone his figuration, and demonstrate that he is an artist of strength and fineness.

(Bombay: Novermber 2007)

Ranjit Hoskote is an Indian poet, art critic, cultural theorist, and independent curator.